D-Lib Magazine

May/June 2017

Volume 23, Number 5/6

Table of Contents

On the Record, All the Time: Audiovisual Evidence Management in the 21st Century1

Snowden Becker and Jean-François Blanchette, Department of Information Studies, University of California, Los Angeles2

becker [at] gseis.ucla.edu; blanchette [at] ucla.edu

https://doi.org/10.1045/may2017-becker

Abstract

We are currently witnessing the explosive growth of audiovisual evidence generated by widespread deployment of surveillance cameras, smartphones, and bodycams in law enforcement. With this growth comes new and emergent intersections of policy, technology and record-keeping in contemporary society. Library and Information Science (LIS) practitioners' expertise in the ethical management of public records has renewed relevance for audiovisual evidence, which requires complex tradeoffs between the competing demands of public access, privacy, cost, and collective memory. This paper reports on the IMLS-funded "On the Record, All the Time" project, which brings together leaders from LIS education, records management, law enforcement, civic governance, and policymaking communities to define the challenges of, and set specific priorities for, the management and preservation of new forms of audiovisual evidence. The project places particular emphasis on identification of core competencies for managers of audiovisual evidence. It also seeks to facilitate information exchange and radical collaboration with key stakeholders--notably, law enforcement and criminal justice practitioners--with whom the LIS field has previously had little contact, and to open new areas of research and professional possibility for LIS program graduates.

Keywords: Body-worn Cameras, Preservation, Audiovisual Evidence, Education

1 A Crowd Forms in Dallas

In Dallas, Texas, crowds of people from all over the country gather as spectators and supporters, to be part of something memorable, even historic. At a time when racial tensions are peaking nationwide, it is important for these people to be here together on this day. Thousands of them line the downtown streets. Then, without warning, a sniper fires his weapon from above; chaos, confusion, anger, and grief quickly follow. Federal, state and local law enforcement reach out immediately, along with the media, to those who witness the event in an effort to establish just what happened and why.

This description applies not only to the events of July 7, 2016, when a gunman targeted Dallas police during a public demonstration, but also to November 22, 1963, when President John F. Kennedy was assassinated. Then, as now, people captured the events of the day on camera — the moments before and after shots are fired, the times when citizens encounter the state in violent and lethal ways. People create records that become evidence, evidence that becomes history. As we passed the 25th anniversary of motorist Rodney King's apprehension by LAPD officers, we were reminded that footage of that incident was crucial to the use-of-force trial of the arresting officers, and then took on an iconic meaning far removed from its original context (see WITNESS, 2017). It is highly likely that video files now regarded as ephemeral or disposable will have a much longer useful life than anticipated, along with dynamic needs for secure management, storage, and ethical use. In short, the challenges in audiovisual evidence management are not new, but venerable.

Figure 1: Frame 371 of the Zapruder film (Wikimedia, 2008)

Among those challenges are material and mechanical ones: What are the critical affordances of our recording technologies, their capabilities and limitations? What falls beyond the frame; what gets redacted or corrupted? Four frames of the original Zapruder film were, famously, damaged by LIFE magazine photo technicians during copying. Two other frames appeared out of sequence in the original printed version of the Warren Commission Report. In every frame of the 8mm original, there is exposed image area between the sprockets — which, as can be seen here in Figure 1, captures important information about the scene as it unfolded, but which is not visible during regular projection. In a climate of suspicion and distrust, any missing, hidden, or altered data quickly becomes fodder for conspiracy theories. It is impossible to restore integrity to a broken chain of custody, or authenticity to an altered original.

Other challenges are informational and access-related: What right do the people and the press have to see and circulate images of significant events? What ethical guidelines govern the use of these images in news, in entertainment, in the social sphere? We continue to struggle now with discussions of what images we may see and what images we might not want to see — and with the morality of sharing those images, or profiting from violent death as spectacle (Juhasz, 2016; Noble, 2014).

Finally, these records pose custodial and curatorial challenges: Who takes responsibility for the preservation of these recordings? What happens to their material forms and social meaning over time? How do the acts of classification and designation as public records dictate these recordings' disposition, and what kinds of value do we ascribe to them? The U.S. government effectively asserted eminent domain over the original Zapruder film, designating it an "assassination record" under the 1992 John F. Kennedy Records Collection Act. In the case of the Zapruder film and its contemporaries, the original materials are stored by archives and museums — but what about the records we are all generating today of the stories that dominate our headlines? How do we secure their survival for the next fifty-three years? Records retention policies and the legal "duty to preserve" extend only to what must be kept; they do little to address what should be kept, and by whom, or how to move beyond basic compliance and toward responsible stewardship.

What's more, the widening gap of trust between communities — especially communities of color — and those empowered by the social contract to wield force in the cause of keeping the peace has made it difficult to find common ground. Whatever echoes there may be between the past and the present, 2016 is not 1963. We are now working in a media and technology environment that is incredibly swift-moving, and unprecedentedly powerful. It is a difficult time to take on complex problems for which solutions may be a long time coming. It is a difficult time to be making and collecting records whose fixity, durability, and authenticity are suspect. And it can be difficult, as well, to confront the succession of news events and the lengthening list of names of the fallen that are connected to these issues, and that continually redefine the boundaries of this topic.

This paper reports on the IMLS-funded "On the Record, All the Time" project, which brings together leaders from Library and Information Science (LIS) education, records management, law enforcement, civic governance, and policymaking communities to define the challenges of, and set specific priorities for, the management and preservation of new forms of audiovisual evidence. In particular, the project focuses on identifying core competencies for those entrusted with the care of evidentiary recordings. This project also aims to facilitate information exchange and radical collaboration with key stakeholders — notably, law enforcement and criminal justice practitioners — with whom the LIS field has previously had little contact, and to open new areas of research and professional possibility for LIS programs and their graduates.

2 LEOs Meet LIS

Law enforcement organizations (LEOs) are increasingly information-centered and data-driven bodies (President's Task Force on 21st Century Policing, 2015b). They have also been among the first entities to encounter and grapple with the implications of new recording technologies — from surveillance cameras continuously recording public and private spaces to bystanders uploading smartphone-generated videos to YouTube. LEOs are under increasing pressure to adopt body-worn cameras (BWC) as a means of increasing transparency and accountability, especially with respect to minority populations adversely and disproportionately affected by encounters with police in the U.S. Yet, as Lum and Koper (2015) note, BWC programs are still in their formative stages, and police agencies nationwide are deploying BWCs in a data-poor environment.

Adoption of new technologies creates new costs, and demands new skills, systems, and resources — the full extent of which are still unknown for BWCs. In Los Angeles alone, the LAPD has estimated that 122 new staff positions will be needed to manage the increased workload associated with deploying 7,000 cameras. This prediction has raised concerns in local government and delayed city approval of BWC program plans (Mather, 2016). NYPD figures released last year estimated costs of reviewing and redacting BWC footage prior to public release at $120 per hour (Kravets, 2016). Each instance raises fundamental questions about who will manage the large quantities of video data generated under BWC programs, what their roles and responsibilities will be, what tools they will use, and how they will interact with existing criminal justice systems and technology infrastructure. Timely intervention, inclusion of diverse voices, and advocacy on the part of information professionals for long-term planning at this critical time will significantly shape the management and preservation of these documents in the future.

Some LIS, media studies, and criminology programs in North America have begun to address evidence in their curricula in ways that transcend the traditional records management focus on textual records and regulatory compliance. In 2010, for example, the University of British Columbia's School of Library, Archival, and Information Studies, UBC Faculty of Law, and Vancouver Police Department's Computer Forensics Division collaborated on a Digital Records Forensics research project, whose goals included "the integration of digital forensics with diplomatics, archival science, information science and the law of evidence." (Duranti and Endicott-Popovsky, 2010) The University of Colorado, Denver's National Center for Media Forensics currently offers a MSc in Recording Arts with emphasis in Media Forensics, while the University of Maryland offers an online MS in Digital Forensics & Investigations. Other institutions including for-profit colleges and trade schools offer certificate programs or courses of study in forensic science, digital forensics, and criminal justice.

On the other side of the equation, law enforcement personnel, including forensic investigators and property and evidence managers, have become increasingly professionalized with the establishment of national groups such as the American Society of Crime Lab Directors (ASCLD), the International Association for Property and Evidence Inc. (IAPE), and statewide property and evidence management associations. Certification, professional training and continuing education, outreach, and cooperation with judicial bodies are among the functions of these groups — for example, the Public Agency Training Council (PATC) offers continuing education workshops for criminal justice practitioners, including recent webinars and training sessions on body cameras. Individual police departments are increasingly partnering with other entities in these efforts, and initiatives including the Department of Justice's Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) and Office of Justice Programs have highlighted evaluation and ethical implementation of body-worn cameras in their funding priorities. The Scientific Working Group on Digital Evidence (SWGDE) includes a Video Committee in its structure, and produces best practices documents and guidelines for forensic retrieval and storage of digital evidence from a wide range of devices and recording media.

Statutory retention periods for criminal evidence vary from state to state; they may range from just a few months to perpetuity, in the case of capital crimes and violent felonies. To date, though, no degree programs or professional organizations have comprehensively identified, let alone addressed, the emergent core-skills training and continuing education needs of information professionals who will be responsible for long-term stewardship of evidentiary recordings. Archivists and audiovisual preservationists, meanwhile, are focused on the organization and long-term access to recordings with evidentiary value, but have not been strongly connected with legal evidence practitioners. When law enforcement agencies and archives do interact, it has tended to be at the point when decades-old criminal justice system records (crime scene photographs, training materials, etc.) are transferred to municipal archives or county historical collections. Faced with daily operational pressures, few police agencies can devote resources to institutional history.

This apparent gap between communities of practice represents an area of opportunity and need that LIS practitioners are well-equipped to fill. As Shannon Mattern points out in "Public In/Formation," "librarians have ... guided patrons through new digital terrain for decades." (Mattern, 2016) Mattern argues that, with public spaces increasingly saturated with information technologies and, in particular, recording technologies, it is time to "push our civic leaders to bolster their planning teams with experts in the ethical collection, organization, preservation, and dissemination of information resources. ... Librarians on the planning commission! Archivists in the police academy! Why not?" (ibid) The "On the Record, All the Time" forum aimed to explore such questions and collaborations, identifying areas of shared concern and bridging disciplinary boundaries. While the answers that emerged underscored the complexity of audiovisual evidence and its long-term management, the conversations proved promising.

3 Starting the Conversation

In August 2016, the UCLA Department of Information Studies brought together multiple academic and professional stakeholders in a National Forum funded by the Institute of Museum and Library Services (see Figure 2). Participants in the forum represented a

wide variety of stakeholder groups, including law enforcement agencies (LAPD, Long Beach PD, IACP, LEVA, etc.); public policy analysts; camera and storage vendors (Taser, Safariland, Amazon, etc.); civil liberties and human rights organizations (Witness, ACLU), archival scholars and digital preservationists. They were tasked with answering a simple question:

"What will people working with large volumes of video data now, and in the future, need to know and do?" We focused on body-worn cameras as a timely example of the complex new forms of evidence that information professionals must be prepared to manage.

Figure 2: Danny Gomez, Tactical Technology Section, LAPD; Jenner Holden, TASER International; Jason Lustig and Gregory Frum, LA County District Attorney's Office, at the "On the Record, All the Time" National Forum, UCLA Young Research Library, August 17, 2016. Image courtesy of the Department of Information Studies, UCLA.

This question points to issues of interoperability, sustainability, and preparedness — issues that were also raised by IMLS National Digital Platform (IMLS, 2015), which lists "radical and systemic collaboration" as a key theme for digital platform development. In a similar vein, the Interim Report of the President's Task Force on 21st Century Policing urges police forces to "[interact] with a more diverse group of professionals ... establish[ing] a valuable network of contacts whose knowledge and skills differ from but complement their own" (2015a, p. 55). The forum was thus designed as a cross-community dialogue aimed at setting priorities for education and training that would address the areas of greatest need for the growing number of information professionals who will be working with audiovisual evidence. We organized the participants in six working groups corresponding to major dimensions of the issue:

- Retention and preservation: defining retention schedules for different categories of footage; planning for the long-term preservation of audiovisual materials;

- Chain of custody and authenticity: formulating or adapting processes that ensure the reliability of evidence in new forms; assuring validity and trustworthiness among user communities that include prosecutors, defense, and the public;

- Public access and privacy: responding to requests for release of public records, while managing privacy rights of concerned individuals;

- Community and culture: facilitating public understanding of the characteristics and constraints of audiovisual evidence; responding to the proliferation of both bystander video and police-generated recordings; anticipating the transmission and interpretation of recordings of police encounters from multiple sources through mass media;

- Technology: evaluating the various characteristics of both hardware and software systems and their impact on the quality of evidence; imagining the future evolution of such systems; measuring the need for and impact of new capabilities — e.g., computational analysis of footage, automated tagging, event logging, or redaction;

- Economic models: supporting the accurate estimation and justification of the up-front costs of hardware, software, and storage systems; commitments to ongoing management, upgrades, and technological change; resources and training required for full and timely responses to public records requests.

For each of the topics above, participants focused on four main questions:

- Content and resources: What would a course of study on this topic look like?, e.g., key learning objectives and modules? What essential readings or resources (e.g., annotated bibliographies) are available or might need to be developed? What theoretical and empirical research is available or needed in this area?

- Certification and credentialing: What would constitute competence in this area, and how would it be most effectively evaluated (e.g., examination, certification, credentialing)?

- Delivery channels: What is the most appropriate mode of delivery for training or information in this area? What existing mechanisms can be expanded or used as models (e.g., graduate/undergraduate degree programs, certificate programs, continuing education credits in conjunction with certification, workshops, summer institutes)?

- Funding: What funding/financial models exist for people to receive training (e.g., Coverdell grants, targeted recruitment fellowships, etc.), and what might still be needed? What groups, individuals, and entities might be our partners in this?

While we are still synthesizing into a white paper the rich answers workshop participants provided to these questions, some preliminary findings were immediately clear and can be summarized here.

4 Preliminary Results

The National Forum meeting was, first and foremost, an unprecedented opportunity for stakeholders from multiple sectors to share space, perspectives, and experience. Criminal justice researcher Michael Buerger (2010) has referred to policing and research as "two cultures separated by an almost-common language"; Bradley and Nixon (2009) similarly make a distinction between research on the police and research with the police. This distinction was clear to project organizers as we worked to identify and recruit potential participants. It seemed that few law enforcement personnel or vendors had ever been contacted by academics to talk about their work. While some had been part of symposia or working groups on BWC programs within their own communities, none had been invited to take part in an interdisciplinary discussion such as we proposed. Community advocates and civil liberties groups, on the other hand, have often found themselves in oppositional relationships with police representatives, or stonewalled by vendors protective of their proprietary technology. With fresh police-footage stories appearing in every news cycle, opportunities to consider the larger context and long-term impact of new technology deployment had been rare for all of us. It therefore mattered a great deal that the National Forum was neither a press briefing during a crisis situation, nor a vendor's sales pitch or training session, nor an academic conference focused on delivering research papers. The Forum was for many participants a unique opportunity to speak directly and openly with a BWC system vendor, a forensic evidence examiner, a digital archivist, or a free press advocate. Participants could exchange and compare descriptions of their work practices in specific local contexts, and frame their encounters with BWC recordings as creators, requestors, or viewers.

Secondly, the person-to-person, small group, and plenary conversations of the National Forum all helped convey a more holistic perspective on the entire lifecycle of BWC records — from design and pricing of the cameras and storage systems to piloting their use in the field, developing policy for recording, retention and disposal, and requesting access to stored recordings. Our discussions highlighted the fact that many data management practices within law enforcement (not just those related to BWC footage) are ad-hoc, responsive to a fast moving and localized technological and regulatory environment rather than high-level strategic priorities. As with workflows in many other digital records systems, these data management practices are seldom codified or even documented. Many procedures are tacitly conveyed and transmitted through hands-on training; others are black-boxed, especially when software and storage services are provided by third-party vendors. The Forum thus revealed the enormous need for identification, articulation, and formalization of such practices in policy and training alike.

In addition to bridging disciplinary gaps and identifying process shortfalls, discussions among participants helped to identify areas of common interest. Law enforcement agencies and LIS institutions alike are public-facing, service-oriented, and vested with a public trust. Indeed, there are several precedents for collaboration between LIS institutions and the criminal justice system: prison libraries are steady employers of LIS program graduates, municipal archives manage records of police alongside those of other city agencies, and police departments rely on records managers and designated staff for servicing open records requests. Both fields are also deeply invested in and affected by larger trends in information technology and information policy, be that the transition from paper to electronic records, crowdsourcing of surveillance or resource description, or datafication of their practices. In spite of the current gap between these two communities, there were thus commonalities from which further collaboration could be developed.

4.1 Applying findings to practice

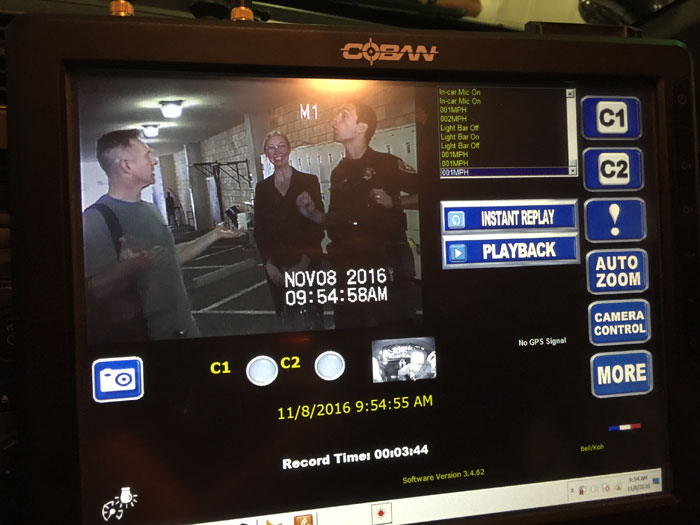

Immediately after the National Forum, we had the opportunity to put in practice some of these findings in the form of a graduate course on surveillance, data management, and record-keeping, offered under the Media Archival Studies specialization track in UCLA's MLIS program. Many connections made during and through the forum were developed into resources for the course. We experimented with cloud-based home security cameras from Nest and sample body-worn cameras from Vievu, and visited the UCLA Police Department to observe their in-car, personal, and in-station recording systems in situ (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: MLIS student Kip Holcomb, co-instructor Snowden Becker, and Officer Justin Bell in the sally port of the UCLA Police Department, viewed through the dash-mounted camera display interface of a patrol vehicle. Image courtesy of Caitlin Meyer.

A cross-section of stakeholders similar to those who participated in the National Forum addressed the class as guest speakers, and their presentations frequently echoed the conversations and discoveries made during the National Forum, in particular those related to the often pragmatic, ad-hoc nature of data management work and policies related to surveillance technology. For example, we heard from Matthew Barrett, a UCLA MLIS alumnus who manages a surveillance camera program for the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (Metro) that dwarfs any proposed police BWC program: over 2300 buses, each equipped with 6 to 12 cameras and DVRs with anywhere from 3 to 7 days of continuous recording capacity. Each month, footage from about 1000 incidents is extracted, burned to DVDs, and stored for two years in fulfillment of public records requests, criminal proceedings, and insurance investigations. Barret's presentation demonstrated a very different application of surveillance technologies by a public agency, while underscoring the demands and limits of surveillance capabilities. Among Metro's challenges: the continuous need for maintenance, the labor involved in extracting the relevant footage from vehicle DVRs and moving it to more durable media, and meeting the demand for public records with the low staffing typical of records departments. Barrett's remarks underscored that, despite its enormous size and scope, Metro's surveillance program is under-funded, subject to significant breakdowns, and driven more by pragmatic liability concerns rather than an Orwellian scheme of social control.

In another presentation, forensic video examiner Marla Carroll showed the class an excerpt from a VHS surveillance tape, a key piece of evidence in a robbery murder case that unfolded, through multiple convictions, appeals and reversals, over a span of thirty years. She described how she had watched it hundreds of times in preparing and enhancing the exhibit for jury review, working to ensure relevant material was not obstructed by noise, graininess, or other artifacts of the recording process. She stressed the need for the original recording (on now-obsolete media) to remain playable, as juries want to be able to compare enhanced evidence with the source material. The challenges she faced were clearly in line with those encountered by digital preservationists, balancing the need to alter original bitstreams in migration strategies with that of aligning the process with traditional notions of authenticity.

Beyond affirming the continued benefits of dialogue across communities of practice, another major benefit of the course was that we began to articulate, together with our students, some of the ethical dimensions of archivists' work at the intersection of law enforcement and LIS. This was particularly relevant and challenging for us, given that our department has core values related to equity of information service and social justice in diverse communities. The faculty and students in the department have strong contacts among activist leaders and community-based groups in Los Angeles, but connections within law enforcement are very few. The class, and the larger matter of LIS's role in the future of audiovisual evidence management, thus raised difficult questions. What happens when agendas of progressive change are met by institutions that are conservative, paramilitary, and reactive by nature? How does a culture focused on inquiry and critical reflection work with one that relies on obedience and compliance? The timing of the course during a presidential election that sharply divided political sensibilities made it even harder to articulate an ethical position that didn't revolve around resistance to state power. And while it wasn't difficult to quote Foucault in the service of critiquing the excesses of government surveillance and police force, alternatives modes of engagement didn't present themselves so readily.

5 Next Steps and Conclusion

The deployment of BWCs in law enforcement has been framed as a technological solution that could provide a rare "win-win" for law enforcement and civil liberties (Stanley, 2014): the evidence they provide could minimize spurious claims and lawsuits while serving as a check on police misconduct. Yet implementation of BWC programs proceeds in a "low information environment" (Lum and Koper, 2015), driven by an ongoing series of politically-charged incidents rather than sustained analysis of benefits and trade-offs. Indeed, Wasserman (2014) argues that BWCs represent an instance of a "hasty response to moral panic" (p. 832), and that "the public discussion needs less absolute rhetoric and more open recognition of the limitations of this technology" (p. 833). In the civic sphere, BWCs have become part of what Mattern (2016) refers to as an "ideology of data solutionism," one that has "taken over city halls, planning departments, law enforcement agencies, and countless other domains of public life." Despite bodycams' promise as a tool for accountability, such accountability does not automatically emerge from their deployment. We have yet to determine what kinds of policy will best balance the competing needs for privacy and transparency with practical, technical, and financial limitations.

Furthermore, we must look beyond the technology as it stands today and anticipate that creation of large corpora of records will invite new uses for those records. As cameras' communication and computational capability increases, their recordings will be subjected to various forms of computational analysis, including personal identification and event detection, in real-time and retrospectively. Taser, for example, recently announced its new "Axon AI platform," which promises to quickly isolate and analyze "the most important seconds of footage from massive amounts of video data ... making the visual contents in video searchable in real time." (TASER, 2017) Rick Smith, CEO and co-founder of TASER, further stated that "We believe it's time for video data to move to the center of public safety records systems, with far richer and more transparent information than historic text-only systems ... Axon AI is focused on extracting usable information from these video records, automatically populating our new RMS [records management system]." Clearly, vendors have no intention of treating BWC footage just as static records; they approach them as vast stores of data, ripe for further mining. Indeed, vendors such as TASER have a clear and articulated vision for the future role of recordkeeping in law enforcement, a vision clearly driven by advances in computational capabilities. This vision deals with concerns at the heart of our profession: the relationship between different types of records, the role of metadata and classification, appraisal and determination of value, transparency in record-making and record-keeping systems, etc. If we wish this vision not to remain exclusively vendor-driven, far more active engagement of the archival community with stakeholders, at the level of practice, education, and policy making, is needed. Indeed, archivists must actively shape this new environment.

Compared to its experience with textual records, the collective experience of the archival profession with the management of audiovisual evidence is limited. But archivists have, more than most, the benefit of historical awareness — which includes awareness of change over time in the theoretical underpinnings of our professional practice. As a field, archives and archivists have long since moved away from being passive recipients of records (the "handmaidens of historians") and toward a more strategic and anticipatory approach to records creation, collection, and preservation. Yet the assertion made by Don Page over three decades ago stands: "Policy makers are not in the habit of calling in archivists when decisions are being made." (Page, 1983) As a community of teachers and learners, we can also be leaders. We can initiate work with stakeholders to develop the skills, tools, and trained personnel that will be required to meet the records management needs we have identified. We have much expertise to bring to this complex topic; we do the public a disservice by failing to innovate in the face of new and unprecedented challenges.

Notes

| 1 |

This work was made possible by a Laura Bush 21st Century Librarian Grant (#RE-43-16-0053-16) from the Institute of Museum and Library Services, and the UCLA Graduate School of Education and Information Studies Dean's Student Support Initiative. We sincerely thanks Emily Reynolds and Trevor J. Owens for their helpful feedback. |

| 2 |

This publication is a work of shared authorship. Becker and Blanchette have worked collaboratively on projects related to this topic for an extended period and contributions from both are reflected in this piece. In general, Becker's research focuses on issues of media preservation and longevity and the archival aspects of evidence management work; Blanchette's work focuses on the development of computing infrastructure and electronic records as documentary proof. On joint publications, the authors have chosen to be listed in alphabetical order regardless of relative contribution to the published work. |

References

| [1] |

Bradley, David, and Christine Nixon. 2009. "Ending the 'dialogue of the Deaf': Evidence and Policing Policies and Practices. An Australian Case Study." Police Practice and Research: An International Journal 10 (5–6): 423-35. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614260903378384 |

| [2] |

Buerger, Michael E. 2010. "Policing and Research: Two Cultures Separated by an Almost common Language." Police Practice and Research 11 (2): 135-43. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614261003593187 |

| [3] |

Duranti, Luciana, and Barbara Endicott-Popovsky. 2010. "Digital Records Forensics: A New Science and Academic Program for Forensic Readiness." In Proceedings of the Conference on Digital Forensics, Security and Law 2010, 109–21. St. Paul, Minnesota: Association of Digital Forensics, Security and Law. |

| [4] |

"IMLS Focus Summary Report: National Digital Platform | Institute of Museum and Library Services." 2015. |

| [5] |

Juhasz, Alexandra. 2016. "How Do I (Not) Look? Live Feed Video and Viral Black Death." JSTOR Daily. July 20. |

| [6] |

Kravets, David. 2016. "Police Department Charging TV News Network $36,000 for Body Cam Footage." Ars Technica. January 17. |

| [7] |

Lum, C., Koper, C., Merola, L., Scherer, A., & Reioux, A. (2015). Existing and Ongoing Body Worn Camera Research: Knowledge Gaps and Opportunities (Report for the Laura and John Arnold Foundation). Fairfax, VA: Center for Evidence-Based Crime Policy, George Mason University. |

| [8] |

Mather, Kate. 2016. "LAPD Tries to Answer City Hall's Lingering Questions about Buying Body Cameras." Los Angeles Times, March 22. |

| [9] |

Mattern, Shannon. 2016. "Public In/Formation." Places Journal, November. https://doi.org/10.22269/161115 |

| [10] |

Noble, Safiya Umoja. 2014. "Teaching Trayvon." The Black Scholar 44 (1): 12-29. https://doi.org/10.1080/00064246.2014.11641209 |

| [11] |

Page, Don. 1983. "Whose Handmaiden?: The Archivist and the Institutional Historian." Archivaria 17 (Winter 1983-84) pp. 162-172. |

| [12] |

President's Task Force on 21st Century Policing. 2015a. "Interim Report of the President's Task Force on 21st Century Policing." Washington, D.C.: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services. |

| [13] |

President's Task Force on 21st Century Policing. 2015b. "Final Report of the President's Task Force on 21st Century Policing." Washington D.C.: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services. |

| [14] |

Stanley, Jay. 2014. "Police Body-Mounted Cameras: With Right Policies in Place, a Win For All." American Civil Liberties Union. |

| [15] |

TASER. 2017. "TASER Makes Two Acquisitions to Create 'Axon AI.'" February 9. |

| [16] |

Wasserman, Howard M. 2014. "Moral Panics and Body Cameras." Washington University Law Review 92: 831. |

| [17] |

WITNESS. 2017. "The lasting effect of video capturing the beating of Rodney King." March 3. |

About the Authors

Snowden Becker is Program Manager for Moving Image Archive Studies at UCLA. Her research and teaching focus on the preservation of audiovisual materials as evidence and as part of our larger cultural heritage. Recent projects include her forthcoming dissertation, Keeping the Pieces: Evidence Management and Archival Practice in Law Enforcement, which draws on nine months of participant observation in the Major Crimes Unit of Travis County Sheriff's Office in Texas. She earned certification from the Texas Association of Property and Evidence Inventory Technicians in 2007. Becker is a former Secretary of the Board of the Association of Moving Image Archivists and co-founder of Home Movie Day and the Center for Home Movies.

Jean-François Blanchette is an Associate Professor in the Department of Information Studies at UCLA. He has been researching issues relative to electronic authenticity, computerization of bureaucracies, and the evolution of the computing infrastructure for the past 15 years, including long-term ethnographic work in the French legal professions. He is the author of Burdens of Proof: Cryptographic Culture and Evidence Law in the Age of Electronic Documents (MIT Press, 2012) and co-editor of Regulating the Cloud: Policy for Computing Infrastructure (MIT Press, 2015).