|

|

|

| P R I N T E R - F R I E N D L Y F O R M A T | Return to Article |

D-Lib Magazine

March/April 2016

Volume 22, Number 3/4

Transforming User Knowledge into Archival Knowledge

Tarvo Kärberg

University of Tartu and National Archives of Estonia, Tartu, Estonia

karberg@ut.ee, tarvo.kargerg@ra.ee

Koit Saarevet

National Archives of Estonia, Tartu, Estonia

koit.saarevet@ra.ee

DOI: 10.1045/march2016-karberg

Abstract

The users of archives have a vast body of knowledge about the records held in the archives. Some users have participated in the events, some have known the persons involved, some are experts in the subject matters. Their knowledge can cover important gaps that exist in archived knowledge. The objective of this paper is to explore methods to capture user knowledge and transform it to archival knowledge. We investigate the theory and describe the practical implementation developed at the National Archives of Estonia (NAE). In the theoretical part, we discuss the concept of knowledge and analyse its handling in the Open Archival Information System (OAIS) reference model. Having a clear focus on practical usability we identify a way to improve OAIS: complementing the model with a new link between Access and Data Management functional entities enables more efficient updating of descriptive information. Moving to practice, we describe the initial situation at the NAE, the needs, the approach taken and the solution — the new Archival Information System AIS 2.0. We explain key aspects of the system, including the use of 5-star Open Data in attaining the goal of knowledge transformation.

Keywords: Digital Preservation, Open Data, Knowledge, Crowdsourcing, OAIS

1 Introduction

The Open Archival Information System (OAIS) defines long term preservation as the act of maintaining information independently understandable by a designated community (OAIS 2012, page 1-13). It can be very difficult to achieve this in practice, as the information may have been insufficiently described and structured during pre-ingest or ingest for a number of reasons. For example, if the producer organisation no longer existed at the time of archiving, the desired quality level for submission might have been impossible to reach. Another reason could be related to the available resources. If the producer is unable to devote sufficient resources to transfer properly, but despite that, the archives has interest (or is obliged) to acquire the records, then a possible compromise is transferring the information in less than ideal quality. And indeed, archival organisations have acquired records at highly varying levels of quality.

Therefore, it makes sense to distinguish between three basic terms: data, information and knowledge, as in the DIKW (data, information, knowledge and wisdom) model. Some of the material in archival holdings is just pieces of content — discrete facts without explicit relations (Hicks, Dattero, Galup, 2006, page 19) — that can be considered simple data. Some parts of holdings can be seen as information (content, which has relations, an aggregation of data) (Vijayakumaran Nair, Vinod Chandra, 2014, page 70) and some parts may be even called (recorded) knowledge if they are interconnected (Quisbert, Korenkova, Hägerfors, 2009, page 14). This distinction may not be fully approved by all communities of information and archival sciences as there is no commonly agreed definition of knowledge (Harorimana, Watkins, 2008, page 853) and it may be argued that knowledge can only exist in the human mind (Eardley, Uden, 2011, page 17), but in the context of this paper we follow the spirit of OAIS, which considers it possible to incorporate a knowledge base both in a person and in a system (OAIS 2012, page 1-12), implying that it is possible to transfer elements of that knowledge base between persons and systems. Another reason to have a distinction between these terms is that it provides more structure and clarity to understanding the complexity of digital preservation.

By moving towards knowledge (i.e. complementing simple data and information with contextual linking and organisation), we can gain a better overview of the content of archival collections, which in turn allows us to build better (faster, more accurate, user-friendly, personalised, etc.) access solutions and to provide multifaceted access to the archived knowledge.

While metadata is crucial for digital projects, its creation can be labour intensive and time-consuming (Yakel, 2007). As with any metadata, contextual links between records are relatively easy to produce by the creator at the time of creation. The further from creation, the costlier it becomes to achieve, up to the point where (for most of the collections at the archives) it is practically impossible. Archival institutions, especially the ones with a constant flow of new acquisitions, simply lack the staff to process all their vast holdings. Another overwhelming challenge is the depth and width of expertise required for enriching the descriptions.

A good example from Estonia is EÜE — Estonian Students' Construction Corps (fonds EFA.399 and ERAF.9591 at the National Archives of Estonia). EÜE was an important student organisation during the second half of the Soviet era (1964-1991) — it was a medium for exchange of ideas, a hub of counter culture, a management training camp for future leaders, a club for forming friendships that led to the creation of political parties and businesses. The collections contain thousands of photos, most of which lack proper descriptions. Archivists have insufficient knowledge to properly describe the people, places and activities depicted on these photos. It is thus reasonable to turn to the users, i.e. to "crowd source" the knowledge, as the users and archivists together can be more knowledgeable about the archival materials than an archivist alone can be (Huvila, 2007, page 26). Crowdsourcing enables description of content to take place at a detailed level of granularity across a broad range of subjects and collections (Eveleigh, 2014, page 212). And the time is ripe for crowdsourcing: the relation between archives and users is said to have developed from mediation to collaboration (Yakel, 2011, page 257).

2 Archival Software at the National Archives of Estonia

The National Archives of Estonia had an ecosystem of archival software and hardware designed to comply with OAIS. The same system was used for managing analogue and digital records (with the obvious media-specific differences). The catalogue tools were media-agnostic — processing of archival descriptions for analogue records was done using the tools designed with digital records in mind.

NAE had an electronic archival catalogue, AIS (Archival Information System), with at least the mandatory elements from ISAD(G) filled for all descriptive units (International Council on Archives, 2000). The archival descriptions typically had the following characteristics:

- fonds1 level descriptions rather than comprehensive;

- lower levels (series, file, item) filled with only minimal data;

- isolated collections: apart from catalogues that arrange fonds into general categories, there was no way to access records horizontally, i.e. to find similar records across different collections.

There were also media specific catalogue/access systems for photos (FOTIS), video and audio (FIS), maps etc., which also existed in isolation. The need for more flexible access had been stated both by the archivists and external users.

Regarding crowdsourcing, NAE had some positive experience. The earliest step towards crowdsourcing had been made in December 2004 with the launch of the web user interface of AIS. In AIS, a link for giving feedback was placed on every view and this has consistently created about 100 submissions per year, most of them proposals for fixing errors or otherwise improving elements of description. When processing these proposals, the archivist saw the URL to the AIS web interface, but fixing the data required logging in to a separate administrator interface, manually navigating to the record and redacting the necessary elements of description.

Two more experiences were from specialised crowdsourcing projects: The Name Registry and Digitalgud. The Name Registry is a simple web application for indexing names in church records, plus a form for doing searches on the data collected this way. Digitalgud is a two-week photo tagging campaign that takes place every spring on Facebook and is organised by a group of memory institutions.

While all three experiences were positive, there was still a clear understanding of scalability issues. For the AIS feedback form the issue was with the complicated user interface that wasted archivists' time. The Name Registry was free from this limitation, as it was developed with efficiency in mind, but the high development costs were only reasonable for a one-off experiment, not for frequent creation of new crowdsourcing projects. In the case of Digitalgud the development cost was negligible, as the whole solution consisted of a simple Facebook page, but consequently the administration costs were high — photos had to be manually uploaded to Facebook and user contributions received had to be manually entered into archival catalogues. In all cases, the key complexity laid in integration with the existing catalogue systems: how to get the records from catalogues into the crowdsourcing application and how to integrate the user contributions to the catalogues.

In sum, NAE had:

- good classic catalogues, but no faceted classification;

- a perceived need for better access;

- positive experience with crowdsourcing;

- an understanding of the high costs of ad hoc crowdsourcing.

A decision was made to develop a new central catalogue (AIS version 2.0) with faceted classification and crowdsourcing designed into the core — a system that would facilitate knowledge transformation2 in all possible ways.

3 User-to-archive Knowledge Transformation in OAIS

To build the theoretical foundation for such knowledge transformation we need a means to take user input and use it to update archived information. OAIS acknowledges the need to allow users to complement and update the existing information: "It is important that an OAIS's Ingest and internal data models are sufficiently flexible to incorporate these new descriptions so the general user community can benefit from the research efforts." (OAIS, 2012, page 4-53).

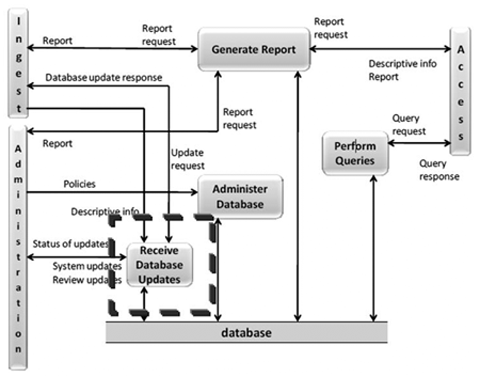

All descriptive data is handled in Data Management and Archival Storage functional entities. The Data Management Functional Entity (DMFE) does not strictly provide anything knowledge-specific, but it encompasses the general logic for updating archival holdings. DMFE is responsible for performing archival database updates. The updates include loading new descriptive information and archiving administrative data as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Data Management Functional Entity (OAIS, 2012, page 4-10)

DMFE includes a Receive Database Update function, which allows for adding, modifying or deleting information in the Data Management's persistent storage. According to OAIS, "The main sources of updates are Ingest, which provides Descriptive Information for the new AIPs (Archival Information Packages), and Administration, which provides system updates and review updates." (OAIS, 2012, page 4-11). The Administration entity is not relevant to our discussion as it deals with the system-related information (generated by periodic reviewing), not the descriptive information of archival holdings. When we look at the enrichment possibilities more closely, we will notice that the Ingest Functional Entity is expected to coordinate the updates between Data Management and Archival Storage (OAIS, 2012, page 4-53). In practice, however, this may involve several complications:

- the enrichment process can involve information from multiple fonds/collections and submissions, but OAIS Ingest is designed for the one-collection-at-a-time principle of receiving;

- performing even small updates still requires running through most of the ingest workflow steps, which is not an optimal use of resources;

- quality control differs: the archivists at the archival institutions are generally not required to check the veracity of Submission Information Package (SIP) descriptions (that is usually the responsibility of the archivists at the producer side), but in the case of crowdsourcing, the updated descriptions proposed by users have to be manually double-checked and confirmed before being accepted as part of official archival descriptions.

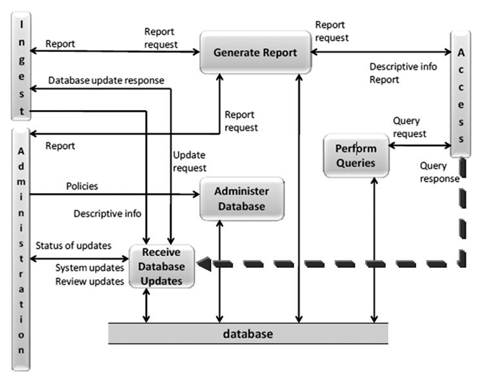

These reasons can in some cases make the Ingest functional entity not scalable enough for updating descriptions via crowdsourcing. We acknowledge that the complications are not critical for every use case, but for the needs of NAE it made sense to look for a more efficient solution. We complemented the OAIS model by adding a direct connection from the Access Functional Entity to the "Receive Database Updates" function in DMFE (see the bold dashed arrow in Figure 2).

Figure 2: Updated version of the Data Management Functional Entity (the added pathway is the bold dashed arrow)

The access entity should act as a gateway in interaction with external users. We select and send the information to crowdsourcing in the access entity and also receive the enriched information back through the same channel. Enriched information will be sent via direct connection from the Access Functional Entity to the Receive Database Updates service in DMFE for further actions. This complemented approach for database updates is more intuitive and requires fewer resources than using the full OAIS Ingest workflow. This modification allowed us to entirely bypass the traditional ingest workflows and design the crowdsourcing processes with only the steps that are absolutely necessary.

4 Approach

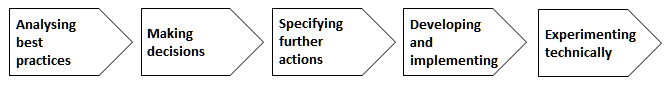

The NAE designed the following plan for creating the tools and processes to allow external parties to contribute to the descriptions of archived information (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Chosen approach

- Analysing best practices — The NAE performed an in-depth analysis of available best practices and standards. The outcome of this task was an overview of the state of the art that fed into the next step — decision-making.

- Making decisions — The NAE decided:

- to complement its implementation of OAIS with a new pathway between the Access and Data Management functional entities (see Section 3 above, describing the theory);

- to publish its restriction-free digital assets as linked open data, i.e. under an open license and in a machine readable form (specifically RDF — Resource Description Framework);

- to improve the structure and linking of the archival descriptions via the transformation of users' knowledge into archival knowledge.

- Specifying further actions — the general decisions from step 2 were split into five technical tasks which are discussed in detail in the sub-sections follow:

- generate Persistent Uniform Resource Identifiers (PURIs)

- publish archival descriptions in machine readable form

- develop software functionality to select records for crowdsourcing

- develop a crowdsourcing tool for the end users

- develop functionality for ingesting crowdsourced information

- Developing and implementing — The applicability of the theoretical model was tested in practice by developing a descriptions' enrichment solution that involved a third party crowdsourcing environment. External tool was selected intentionally, because using only solutions provided by the archives may not be enough for attracting large numbers of contributors (users are comfortable with the tools they use and are not motivated to learn to use new work environments).

- Experimenting technically — a number of experiments were performed in order to guarantee the quality of information flow between components. Technical capability and maturity are important for NAE — technical components should be built in a flexible way to allow processing of different kinds of information.

4.1 Generating Persistent Uniform Resource Identifiers (PURIs)

The NAE decided to create PURIs because they allow unique identification of any resource, independent of the specific information system that holds it. Thereby PURIs improve data longevity — they allow replacement of system components without breaking any references to the information stored in those components.

Another benefit of "PURIfied" information is that it can be aggregated automatically. For instance, the former president of Estonia Lennart Meri was also a writer and film maker, so there are records about him in the National Archives (the fonds of the Chancellery of the President of Estonia), in the National Library and in the Film Museum. If all of these institutions use standardised PURIs, each one of them can provide direct links to the related information in other institutions. If, in addition to using PURIs, the information is published as linked open data (see the next chapter on machine-readable open data), not only the links (PURIs) can be provided, but the actual data can be pulled from other institutions and displayed organically next to the institution's own records. Similarly, independent third parties can build so-called mash-up services, e.g. a hobbyist historian can create an online database of famous Estonians that gathers all the available information from archives, museums and libraries and presents it in an interesting way.

The importance of URIs that are stable in the long term has also been highlighted by the PRELIDA project as one of the burning issues in the digital preservation of linked data (Batsakis, et al., 2014, page 8). In constructing the PURIs we took into account the guidelines and best practices for semantic interoperability (Archer, Goedertier, Loutas, 2012)3 published by the ISA (Interoperability Solutions for European Public Administrations) which were, in brief:

- Follow the pattern. Every URI should begin with the same pattern.

Example: http://{domain}/{type}/{concept}/{reference}

- Re-use existing identifiers.

Example: if schools are already assigned integer identifiers, those identifiers should be incorporated into the URI http://education.data.example/id/school/123456

- Design and build for multiple formats.

A PURI should refer to a conceptual resource, which in turn can have representations in different formats.

Example: the conceptual resource could be identified as http://data.example.org/doc/foo/bar, while its HTML representation could be http://data.example.org/doc/foo/bar.html and RDF representation http://data.example.org/doc/foo/bar.rdf. The latter two are not PURIs, they are resources that are automatically returned to the user who queries the PURI of the conceptual resource, depending on the type of the user (HTML for humans, RDF for machines).

- Implement 303 redirects for real-world objects.

URIs that identify real world objects that cannot be transmitted as a series of bytes (such as places and people) should redirect using HTTP response code 303 to a document that describes the object.

Example: http://www.example.com/id/alice_brown could 303-redirect to a page about Alice Brown.

- Use a dedicated service

The service that resolves the conceptual PURIs to the URLs of actual information systems should be independent of the data originator.

By following these guidelines, we developed PURIs for various content types (Table 1).

Table 1: List of PURIs by resource type

| Type | Description | PURI Structure |

| Description unit | References some description unit (e.g. series). All description units have the same PURI structure. | http://opendata.ra.ee/du/<guid> |

| Subunits | Lists all sub-units of some description unit (e.g. sub-series of series). | http://opendata.ra.ee/du/<guid>/subunits |

| Media list | Lists all digital images that belong to the description unit (e.g. pages of a church book). | http://opendata.ra.ee/du/<guid>/medialist |

| File reference | Reference to a computer file that belongs to the description unit. | http://opendata.ra.ee/media/<guid> |

| Image section | References a selection of some image. | http://opendata.ra.ee/media/<guid>?<x>,<y>,<width>,<height>,<angle> |

| Person | References the description of an archival creator (a person or an organisation). Names of an archival creator may not be unique. In such cases suffixes 1, 2, etc. will be added at the very end of the PURI (e.g. http://opendata.ra.ee/ontology/person/Mart_Saar and http://opendata.ra.ee/ontology/person/Mart_Saar_1. | http://opendata.ra.ee/ontology/person/<name> |

| Location | References to the administrative unit. Administrative units are hierarchical taxonomies which depend on time periods. | http://opendata.ra.ee/ontology/location/<hierarchy> |

| Location subunits | References to the sub-units of an administrative unit. | http://opendata.ra.ee/ontology/location/<hierarchy>/subunits |

| Subject | References to the subject's keyword. Each keyword is unique in the range of its parent. | http://opendata.ra.ee/ontology/subjectarea/<hierarchy> |

| Subject subunits | References to the hierarchical sub-units of a subject's keyword. | http://opendata.ra.ee/ontology/subjectarea/<hierarchy>/subunits |

| Topic | References to the content keyword. Each keyword is unique in the range of its parent. | http://opendata.ra.ee/ontology/topic/<hierarchy> |

| Topic subunits | References to the content keyword. Each keyword is unique inside the scope of its parent. | http://opendata.ra.ee/ontology/topic/<hierarchy>/subunits |

| Photo | References to digital copies of photos. | http://opendata.ra.ee/photo/<guid> |

| Audio | References to the audio objects in FIS (film and audio information system). | http://opendata.ra.ee/audio/<guid> |

| Video | References to the video objects in FIS. | http://opendata.ra.ee/video/<guid> |

| Map | References to the objects in the geographical maps and plans information system. | http://opendata.ra.ee/map/<guid> |

| Parchment | References to the objects in the parchment information system. | http://opendata.ra.ee/parchment/<guid> |

For interoperability reasons, all PURIs were agreed to follow these rules:

- Latin characters, numbers, dashes and hyphens are used as they are;

- Characters "Ü" and "ü" are replaced with "Y" and "y";

- All other characters with diacritics are replaced with their base symbols (e.g. "Õ" -> "O");

- Spaces are replaced with underscores/low dashes;

- All other characters (e.g. brackets, parentheses) are ignored;

- PURIs are case-insensitive;

- All PURIs are created by automated algorithms rather than composed by human actors;

- One object can have more than one PURI.

4.2 Publishing Archival Descriptions in Machine Readable Form

The NAE chose to publish its restriction-free digital assets as linked open data, i.e. in a machine readable form and under an open license. It was a natural decision since the archival law in Estonia sets all archival holdings openly accessible by default. Only a few per cent of the archival records at NAE have access restrictions that stem from data privacy laws and other acts. This open availability covers both the archival descriptions and the digital usage copies (about 15 million files, mostly digitised paper records). The NAE saw open data as an opportunity to better structure and link the archival holdings and a way to facilitate the transformation of users' knowledge into archival knowledge. The view that linked data are a form of formal knowledge was also highlighted by the PRELIDA project (Batsakis, et al., 2014, page 40).

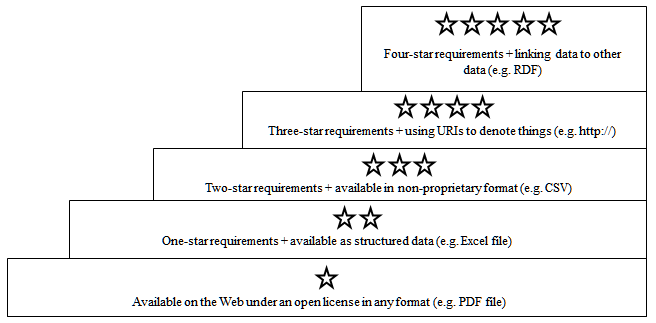

It was decided to observe the five star categorisation model introduced by Tim Berners-Lee (see Figure 4). The model has five levels, each of them describing a set of openness characteristics for data published on the Web. The lowest, one-star level of openness describes any data that is available on the Web under an open license, but is not structured nor easily re-usable. The highest level of five stars is the ultimate in openness: the data is well structured, presented in an open format, described using URIs and linked to other data to provide context.

Figure 4: Open-data star model according to Tim Berners-Lee4

As referred earlier, the NAE decided to present its archival descriptions in RDF (Resource Description Framework) format. Several additional specific standards (ARCH, BIBO, DCPeriod, Dublin Core, FOAF, LOCAH, MODS, OWL, RDFS, SKOS, VCARD) were also incorporated to improve interoperability with other institutions all over the world.

The choice to use RDF was made because it:

- is universal and therefore provides interoperability between Web resource applications in terms of metadata;

- enables automated processing and application of intelligent software agents;

- enables semantic queries, e.g. SPARQL (a recursive acronym for "SPARQL Protocol and RDF Query Language");

- supports creating schemas which can define the meaning, characteristics, and relationships of a resource; can represent digital knowledge;

- is recommended to use in following the requirements for the 5th star open-data categorisation.

All taxonomies (time periods, persons/organisations, subjects, topics, places) were also published as open data. The taxonomies are:

- Time periods. Consists of twelve categories that are essentially named ranges on the time line. The most remote of these is Medieval Era (the oldest records in Estonian archives are from 13th century) and the newest is the Republic of Estonia. For improved usability, the labels of the categories contain both the assigned name of the period and the actual timeframe (e.g. "1918-1940: Republic of Estonia").

- Subject areas. Consists of some domains/fields (e.g. courts of law, associations and movements, schools and education) which can have sub-domains (e.g. the domain "associations and movements" can have the sub-domain "sports federations"). The domains are general and they describe the person or organization whose activities are documented in the archival holdings.

- Topics. Consists of about 2000 keywords. For example, there are record types (e.g. protocol), things (e.g. road), non-administrative places (e.g. farm), concepts (e.g. coastal protection), roles (e.g. fisherman) and activities (e.g. singing). The topics do not duplicate the subject areas (as they describe lower content levels) and other taxonomies (e.g. persons).

- Locations/Administrative units. Consists of places in a hierarchical structure, starting from the largest relevant unit (country of Estonia or the whole world) and going down into as much detail as reasonable (usually town/municipality). Contains five trees with accompanying metadata (e.g. geographical coordinates), of which four are Estonian place name groups organised by time periods (before 1917, 1917-1950, 1950-1991, after 1991), and one tree represents foreign countries organised by continents.

- Persons and organisations. Consists of descriptions of persons and organisations in the ISAAR (CPF) descriptions format and provides additional descriptive characteristics such as Type, with possible values of "Person", "Organisation", "Archival Creator" and "Other."

All published descriptions were also uploaded to a public Web portal to better satisfy the needs of the users of open data. The published archival descriptions include descriptive information of all archival records, no matter whether they are on paper, on magnetic tape or on some other media. The descriptions are hierarchical, starting from fonds level, continuing with series and subseries, and concluding with files and items as proposed in ISAD(G) standard (International Council on Archives, 2000). The descriptions available on higher levels are not repeated on lower levels. In addition to RDF, open data was also published in apeEAD format, which is an elaboration of the EAD standard, created by the Archives Portal Europe project. The format allows gathering all descriptive info of a fonds into one XML file.

The published archival descriptions are available under CC0 licence and digital content under CC-BY-SA licence.

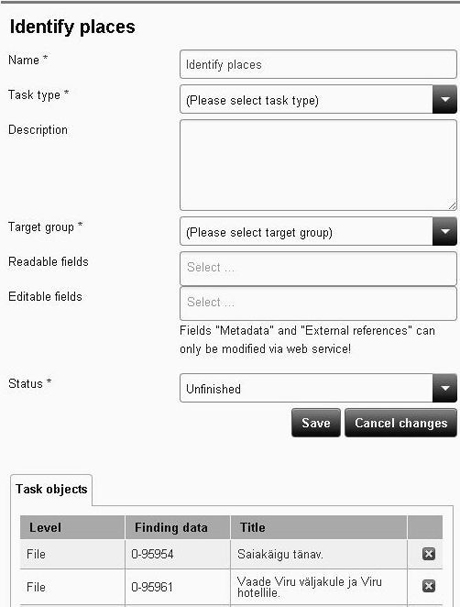

4.3 Developing Software To Select Records for Crowdsourcing

The most logical place for sending information to the specialised crowdsourcing tool is the central archival catalogue, AIS, as it contains all the archival descriptions that can become subject to enrichment. For that reason, a functionality was added to AIS, which allows an archivist to select items in search results and to put them into a special list for crowdsourcing (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Selecting items and metadata for crowdsourcing

The list can be then sent to external tools for crowdsourcing.

The archival access portal provides access to crowdsourcing solutions via HTTP/RDF or SOAP (Simple Object Access Protocol) service. While the HTTP is meant for human browsing, the RDF and SOAP service is more suitable for software applications.

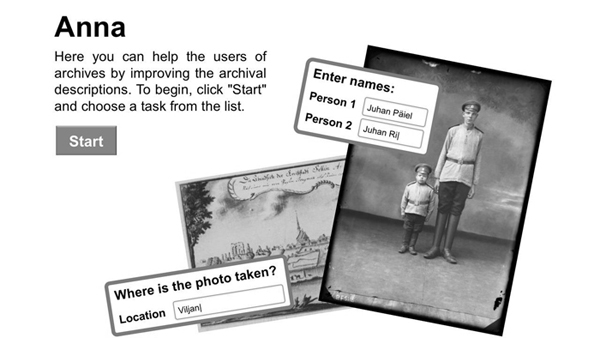

4.4 Developing Crowdsourcing Tools for End Users

Anna

If the list described above is sent to the crowdsourcing tool Anna5 then some additional information should be provided. The archivist can select the target group (including the choice whether to allow participation of users who are not logged in), define and explain the scope of the task (select objects and metadata fields for crowdsourcing) and change the status of the task to public or close it, as seen in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Setting up a crowdsourcing task

Anna allows everyone to contribute to the enrichment process of archival holdings (Figure 7). Contributing is very simple. The user is first presented with the option to log in (login is not mandatory) and select a suitable task. There can be a variety of tasks: ones that ask people to identify the place where the presented photo was taken, others that call for identification of persons on the photos, etc.6

The tasks can also be designed so that the user can select the places or persons from the taxonomy (thereby adding the PURI of the taxonomy item into the metadata of the photo) or if necessary, add new items to the taxonomy (thereby creating new PURIs). Selection from taxonomies is done by searching and browsing, so the user is mostly spared from the complexity of taxonomies and PURIs.

Figure 7: Portal Anna

The tool also has a motivation system which adds a playful, competitive touch to the crowdsourcing. Leader boards and rankings tend to motivate users to participate more, as people want to advance in the rankings and become more recognised in the archival community.

The user score calculated in Anna is not a sum of hours worked or proposals made. It is a sum of points a user earns each time one of their proposals gets approved by an archivist.

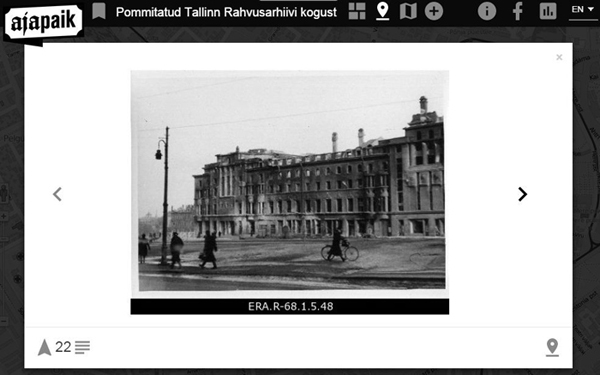

Ajapaik

Anna is not the only option for a crowdsourcing tool — the same methods of task preparation can be used to work with external tools. The NAE has tested this integration with the mashup portal Ajapaik.

The AIS at NAE has the functionality for selecting photos and forwarding the selected set to Ajapaik (Figure 8). Ajapaik allows adding tags (geo-coordinates, camera position, place names) to the photos. These contributions are aggregated using an algorithm that considers users' trustworthiness (based on the accuracy of their previous contributions) and then averages the geo-coordinates. A photo is considered geotagged when enough trustworthy users tag the photo into approximately the same location. Users are then encouraged to visit the location, take a new photo that matches the angle and composition and upload it to Ajapaik, so that an old and a new view can be seen side by side. The metadata collected through this process can be sent to the AIS.

Figure 8: Portal Ajapaik

The portal aims to captivate users by allowing them to add geotags and rephotograph objects, giving the unique opportunity to see what places looked like many years ago and exactly where the photos were taken.

The data exchange protocol for external crowdsourcing tools is based on RDF and PURIs, so the user knowledge can be captured in a well structured form. For example, the geographic coordinates that the users of Ajapaik contribute by simply clicking on the interactive map, can be returned to the NAE's Anna/AIS system in the form of standardised PURIs. These PURIs can later be used to pull together information related to this geographic spot from any online source that also uses standardised PURIs for geo-coordinates. In a similar manner, Ajapaik will store the PURIs it got from the archives in the beginning of the process and can provide its users with links to the related information in NAE's online services.

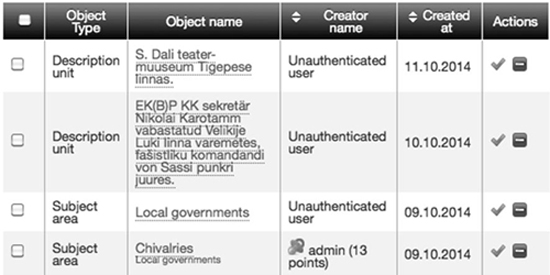

4.5 Developing Functionality for Receiving Crowdsourced Information

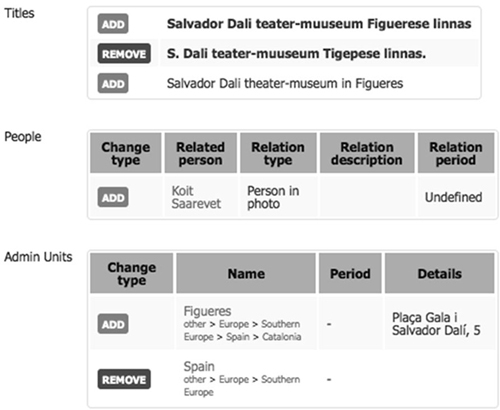

User contributions are received by AIS via a simple SOAP service so it is easy to build this communication capability into new crowdsourcing tools. Inside AIS, the newly imported data is instantly published next to the official metadata, but clearly labeled as "unofficial contributions from users." The same data is also presented to the archivists as a list of proposals to be reviewed (see Figure 9).

Figure 9: List of Proposals

The archivist can examine each proposal in detail (Figure 10) and then reject it, approve it or leave it as it is. Rejection deletes the proposal, while approval makes it part of the official archival descriptions. Rejections and approvals can also be done in batches, to spare the archivist from excessive clicking.

Figure 10: Detailed view of a proposal

5 Combining Components in the Workflow

5.1 Curated Crowdsourcing

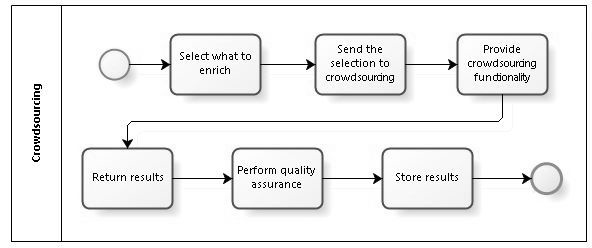

The general business process workflow for crowdsourcing at the NAE can be seen in Figure 11.

Figure 11: Business process workflow for crowdsourcing

The workflow covers the following activities:

- Select what to enrich. The archivist marks the description units or taxonomies that are to be enriched.

- Send the selection to crowdsourcing.

- Local solution. Send the previously made selection to portal Anna, which is maintained by the archives.

- External solution. Send the previously made selection to some external application (e.g. Ajapaik), which can provide various ways to enrich the information. External applications are not maintained by the archives, and therefore the archives don't have control over the enrichment process and should wait until the enriched information arrives back to the archive.

- Provide crowdsourcing functionality.

- Local solution. Portal Anna can be accommodated for a variety of task types and is optimal for tasks that recur frequently (such as identifying persons on photos) — NAE can invest the effort to design a really comfortable user interface. Importantly, Anna has built-in motivation system, so devoted contributors can build their reputation score across various crowdsourcing projects.

- External solution. These can be a good option if they have an active user base or have some attractive features, e.g. in the case of Ajapaik, the ability to add contemporary photos next to the historical ones.

- Return results.

- Local solution. Tasks have fixed deadlines, and after reaching the deadline the results will be delivered to the AIS for review by the archivists.

- External solution. Task deadlines depend on the tool's functionality and and agreements with the external partner. When the results are received, they are presented to the archivists for review.

- Perform quality assurance.

- Local solution. As the entire environment is controlled by NAE, assessing the quality of the contributions might require less effort from the archivists.

- External solution. Here, quality control probably needs more care, e.g. the algorithms to calculate user trustworthiness might not be as reliable as those used by NAE.

- Store results. After the quality control, the user contributions that got approved will be sent to the archival repository and the information enrichment process is over.

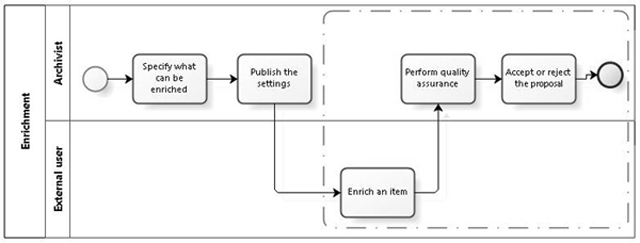

5.2 Spontaneous Crowdsourcing

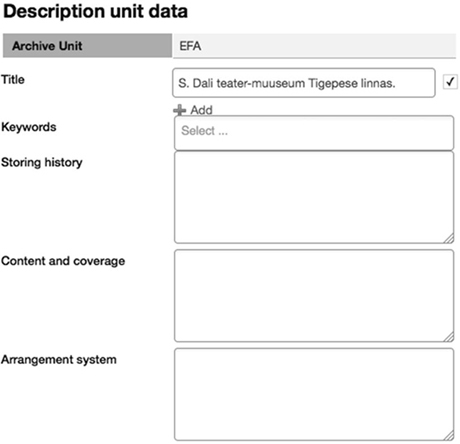

The NAE has noticed that some users do not want to use crowdsourcing tools while they are still willing to share their knowledge if it can be done quickly within their normal work environment. The NAE developed an alternative crowdsourcing workflow that allows users to propose changes to nearly all elements of archival description.

Figure 12: The first few fields of the spontaneous crowdsourcing form

As mentioned above, a simple version of such functionality had been present in AIS version 1 and FOTIS in the form of a "report error" link. The user was provided just one plain text field to describe whatever suggestions they had. While easy to use, this solution was very laborious for the archivists, so there was demand for a more automated process. The new method allows structured proposals, i.e. new values can be suggested granularly, for any individual data field present in AIS. As some elements of description cannot take input from anyone but archivists (e.g. reference codes), it makes sense to hide them from the proposal form. This is why the first two steps of the workflow in Figure 13 are necessary — they set the initial configuration of the system.

Figure 13: Business process workflow for spontaneous crowdsourcing

The workflow consists of the following steps:

- Specify what can be enriched. The archivist selects the data fields that are included in spontaneous crowdsourcing. This is a one time step that needs to be repeated only if the model of archival descriptions is changed.

- Publish the settings. A one time step to enforce the new configuration.

- Enrich the item. The user shares his/her knowledge by clicking "Add proposal" and entering suggestions to the right fields. In case of taxonomy based fields (e.g. the field "Persons on the photo"), the user can search/browse the taxonomy and pick from there or propose an addition to the taxonomy.

- Perform quality assurance. The archivists will have to perform quality checks, as with any crowd-contributed information.

- Accept or reject the proposal. The archivists can choose to approve or reject the proposal. If approved, the information contained in the proposal will be sent to the archival repository and the information enrichment process is over.

6 Conclusions

Our research and practical experimentation confirmed that it is possible to complement the OAIS Data Management Functional Entity (DMFE) to support the descriptive information update more widely and effectively — we can now acquire the contributions of external organisations and individuals using only the necessary specific steps instead of the full complexity of ingest entity. Simultaneously, it became clear that there is synergy between 5-star open data and transformation of user knowledge. Linked open data serves as a great communication interface between crowdsourcing tools, plus, through its inherent linkability helps create attractive mashed-up crowdsourcing environments. In turn, the user contributed knowledge and work hours are a significant force in filling the gaps in archival knowledge and thus improve the quality of linked open data.

It is reasonable to involve external parties in creating and managing the crowdsourcing solutions. There are several advantages. One of them is that the existing solutions may already have their own loyal user community, which means that the archives do not need to spend additional resources to invite people to the crowdsourcing environment.

The described information system was not yet live at the time of print, but the technical tests and experiments performed gave ample reasons to predict good results. As the new solution allows collecting additional descriptive information for multiple dimensions from multiple sources, it gives the NAE the opportunity to receive descriptions in different granularity and quality. The solution is in essence data independent, so it is possible to build very complex relations between information entities without any restricting constraints declared by data types.

Despite the numerous successful technical experiments, real life pilot projects have to be performed as well. Exposing the solution to practice will reveal if the users accept the tools we developed.

The following list summarises the main values of this effort for the archival community.

- Our experience as a case study in moving the archival descriptions and user interaction to a qualitatively new level.

- To our knowledge, AIS 2.0 is the first attempt by a national archives to build a system with such features; specifically, the innovation is in the combination of the following:

- Faceted classification (including searching and browsing) built into the core;

- Using AIS as the central repository for ontologies — all other systems use it via web services;

- Automatic publishing of 5-star open data/linked data, using AIS as the aggregator of data from all the other systems;

- Crowdsourcing capabilities designed into the core, including ways for users to propose changes to any data element, fast and flexible creation of new crowdsourcing projects, motivational scoring, quality management, support for external crowdsourcing tools.

- Using linked data as a means of communication with external crowdsourcing tools;

- Using linked data as a means of interfacing with automated tagging tools (NER — Named Entity Recognition)

Further studies should look into developing standardised ontologies (to improve interoperability of linked data) and standardising the means of communication between catalogue and crowdsourcing systems.

Notes

| 1 | Fonds is the archival term for the whole set of records from a single creator. More precisely: "The whole of the records, regardless of form or medium, organically created and/or accumulated and used by a particular person, family, or corporate body in the course of that creator's activities and functions. /.../ The fonds forms the broadest level of description; the parts form subsequent levels, whose description is often only meaningful when seen in the context of the description of the whole of the fonds. Thus, there may be a fonds-level description, a series-level description, a file-level description and/or an item-level description." (International Council on Archives, 2000, pp 8, 10) |

| 2 | A beneficial side effect of the knowledge transformation machinery is the ability to efficiently crowdsource mundane tasks, such as indexing names from scanned document images, transcribing handwritten text or audio recordings, etc. |

| 3 | This document also contains information about the use of PURIs in some other organisations in Estonia, but for wider interoperability we followed the guidelines described in the document as they have been created, taking into account all other approaches, not only the local ones. |

| 4 | The model has been redrawn based on the model at http://5stardata.info/. |

| 5 | Web portal Anna is a crowdsourcing portal created by the National Archives of Estonia. |

| 6 | The first version of Anna is limited to photos, as only a photo viewer prototype was implemented for content display. However, the design is open for adding viewers/media players and there are no restrictions to the metadata fields. |

References

| [1] | Archer P, Goedertier S, Loutas N (2012). D7.1.3 - Study on persistent URIs, with nameentification of best practices and recommendations on the topic for the MSs and the EC. |

| [2] | Batsakis S, Giaretta D, Gueret C, van Horik R, Hogerwerf M, Isaac A, Meghini C, Scharnhorst A (2014). D3.1 State of the art assessment on Linked Data and Digital Preservation. |

| [3] | CCSDS (2012). Reference model for an open archival information system (OAIS), Consultative Committee for Space Data Systems, Magenta Book. |

| [4] | Eardley A, Uden L (2011). Innovative Knowledge Management: Concepts for Organizational Creativity and Collaborative Design. Hershey, New York. |

| [5] | Eveleigh A (2014). Crowding Out the Archivist? Locating Crowdsourcing within the Broader Landscape of Participatory Archives. Crowdsourcing our Cultural Heritage. Ashgate Publishing, Farnham, UK |

| [6] | Harorimana D, Watkins D (2008). The 9th European Conference on Knowledge Management, Academic Publishing Limited, Southampton, UK. |

| [7] | Hicks R. C, Dattero R, Galup S. D (2006). The five-tier knowledge management hierarchy. Vol. 10 No. 1, Q Emerald Group Publishing Limited. |

| [8] | Huvila I (2007). Participatory archive: towards decentralised curation, radical user orientation, and broader contextualisation of records management. Archival Science. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-008-9071-0 |

| [9] | International Council on Archives (2000). ISAD(G): general international standard archival description. Adopted by the Committee on Descriptive Standards, Stockholm, Sweden, 19-22 September 1999 (2000) 2nd edn. ICA, Ottawa. |

| [10] | Palmer, J (2009). Archives 2.0: If We Build It, Will They Come?. Ariadne, Issue 60. |

| [11] | Quisbert H, Korenkova M, Hägerfors A (2009). Towards a Definition of Digital Information Preservation Object. |

| [12] | Vijayakumaran Nair K, Vinod Chandra S. S (2014). Informatics. PHI Learning Private Limited. Delhi. |

| [13] | Yakel E (2011). Who Represents the Past? Archives, Records, and the Social Web. Controlling the Past: Documenting Society and Institutions (edited by Cook T). Society of American Archivists. Chicago. |

| [14] | Yakel E, Shaw S, Reynolds P (2007). Creating the Next Generation of Archival Finding Anames. D-Lib Magazine, Volume 13 Number 5/6. http://doi.org/10.1045/may2007-yakel |

About the Authors

|

Tarvo Kärberg (Master, Information Technology, University of Tartu) works as a software project manager at the National Archives of Estonia, responsible for software projects of digital preservation for nearly ten years. He has passed the Estonian national certification as an archivist and is academically involved in teaching a course on digital archival holdings and electronic document management at the University of Tartu. He is also responsible for leading the work package on transfer of records to archives for the European Commission Project E-ARK (European Archival Records and Knowledge Preservation). His interest focuses on the theory and methods of collecting and preserving digital knowledge. |

|

Koit Saarevet has been working for The National Archives since 2000, mostly in the capacity of the project manager responsible for the development of various information systems. That includes both the first version of the Archival Information System AIS (i.e. the central catalogue and finding aid system) that went online in 2004 and its successor, the AIS 2.0. Koit has a BA in IT management from Estonian Business School and has studied innovation management at MIT as a Hubert H. Humphrey fellow. |

|

|

|

| P R I N T E R - F R I E N D L Y F O R M A T | Return to Article |